Welcome to the personal homepage of Loïc Wacquant. I am an interdisciplinary sociologist who tries to wed epistemology, ethnography, social theory, and comparison to capture the carnality of social existence; the structure, dynamics, and experience of urban marginality; the making of the penal state and the rise of neoliberalism; the specificity of ethnoracial domination and the predicament of the precariat. (The picture at the left is from back in 2012 but it captures well my intellectual posture).

Below is a selection of recent articles (published in multiple languages) and a presentation of my recent books. To find out where I am at, read Rethinking the Penal State (Polity, 2026); Racial Domination (Polity, 2024); and The Poverty of the Ethnography of Poverty (Oxford University Press, [2023] 2025). When you are tired reading, come enjoy a drink at the Ethnographic Café.

For an overview of the inspiration, trajectory and foci of my work, read “Carnal Concepts in Action” (Thesis Eleven, 2023).

Some recent papers

“Against Abolitionism: The Case for Radical Penal Minimalism.” New Left Review 164, October 2025, in press.

“A Cautionary Note on Race and Criminal Prosecution.” Forthcoming.

“Why Class Discrimination is Invisible.” Forthcoming.

“Sealing the Fate of ‘The Kid’: A Field Note on the Swirl of Plea Bargaining.” Punishment & Society: online.

English (and in a half-dozen languages): “Thinking the Urban with Bourdieu: An Interview with Loïc Wacquant.” Space & Culture.

“Punish to Rule: Colonial Penality and the Urban Badlands.” New Left Review, no. 152,March-April 2025, pp. 111-141.

-“In Praise of ‘Thick Construction.’” Qualitative Sociology, 48 (2024): 335-345. See the symposium with my response: “Catching the ‘Epistemological Virus’: A Response to the Critics of Thick Construction.”

-“Notes on Race as Denegated Ethnicity.” Ethnicities 25, no3 (2024): 474-480. See the symposium with my response: “Farewell to ‘Race and Racism’: On the Analytic Primacy of Ethnicity.”

-“The Checkerboard of Ethnoracial Violence.” Contention: The Multidisciplinary Journal of Social Protest 11, no. 2 (2025): 81-94. See the symposium with my response: “Race in the Violence of Violence: A Reply to the Symposium.”

-“Lessons from the Tall Tale of the ‘Underclass’: A Response to my Critics.” Dialogues in Human Geography, 2024. Response to the symposium on The Invention of the Underclass: A Study in the Politics of Knowledge (2022).

-“The Trap of ‘Racial Capitalism’.” Archives européennes de sociologie/European Journal of Sociology 64, no. 2 (2023): 153-16. See symposium with my response: “Racial Capitalism Decoupled: A Rejoinder and Specification.”

-“What the City Tells Us About Bourdieu and Bourdieu Tells Us about the City.” Dialogues in Urban Research, 2024. Response to symposium on Bourdieu in the City: Challenging Urban Theory (2023).

“Rethinking the City with Bourdieu’s Trialectic.” City 26, no. 5-6 (2023): 820-830.

-“Ruination in the Ring: Habitus in the Making of a Professional ‘Opponent’.” Ethnography.

RECENT BOOKS

CARNAL ETHNOGRAPHY: HABITUS AT WORK

In early 2022, Oxford University Press published the expanded anniversary of Body and Soul: Notebooks of an Apprentice Boxer (with 140 pages of new text). The extended post-face explores “the making of” the study and explicates how I deployed Bourdieu’s signal concept of habitus as both topic and tool of inquiry on the way to formulating the tenets of “carnal sociology.” It also retraces the trials and tribulations of my gym mates in and out of the ring over the past thirty years and probes what they reveal about the economics of blood, masculinity, and love, and about the craft of sociology itself.

PHOTOETHNOGRAPHY AND THE SOCIAL HISTORY OF A BODILY CRAFT

A companion book of historical photo-ethnography was published in September 2022 in France with La Découverte under the title Voyage au pays des boxeurs (Journey in the Land of Pugs). It features a carefully curated selection of 245 black-and-white pictures set into a sociological text of 40,000 words and enlivened by raw quotes from boxers, trainers, and assorted fight people encountered during my three-year sojourn among prizefighters on Chicago’s South Side in 1988-1991. It is an effort to fuse visual art, social history, and literary sociology inspired by James Agee and Walker Evans’s, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941).

Working on this book of photo-ethnography led me to dive in my boxing archives and to immerse myself again in my notes and interviews of the period. One product of this immersion is the article “Ruination in the Ring: Habitus in the Making of a Professional ‘Opponent’,” published in Ethnography (2022), on desire and domination in the workings of the pugilistic economy.

URBAN MARGINALITY, INTELLECTUAL HISTORY, REFLEXIVITY

The Invention of the “Underclass”: A Study in the Politics of Knowledge (2022) is an exercise in epistemic reflexivity in the mold of Bachelard, Canguilhem, and Bourdieu. It charts the rise, metamorphoses, and fall of the racialized folk devil of the “underclass” in the long shadow of the ghetto riots of the 1960s. It draws out the implications of strange career of this academic-journalistic-policy myth for the social epistemology of dispossessed and dishonored categories. It uses this case study to uncover the springs of “lemming effects,” “conceptual speculative bubbles” and “turnkey problematics” in social science. It elaborates a set of criteria for forging robust analytic concepts and applies them to the vexed notion of “race.” This argument is further extended in an article on “Epistemic Bandwagons, Speculative Bubbles, and Turnkeys: Some Some lessons from the tale of the urban ‘underclass'” (Thesis Eleven, 2023).

Virtual Book Talk | The Invention of the ‘Underclass’: A Study in the Politics of Knowledge

On May 4, 2022, NYU’s Institute for Public Knowledge hosted a virtual book talk on The Invention of the “Underclass” via zoom featuring historian Thomas Sugrue, political scientist Kimberley Johnson, and sociologist Neil Gross, moderated by Eric Klinenberg. You can see it there on Youtube.

See also the symposium on the book in Dialogues in Human Geography, including my response “Lessons from the Tall Tales of the ‘Underclass'” (2024).

NEO-BOURDIEUSIAN URBAN THEORY

In 2023, Polity Press published my book Bourdieu in the City: Challenging Urban Theory, which offers a novel interpretation of Pierre Bourdieu through the trialectic of symbolic, social, and physical space. I propose to rethink “the urban” as the domain of the accumulation, diversification, and contestation of capitals, in the plural, and as the grounds for the commingling and collision of variegated habitus, which makes the city a central site and stake of historical struggles.

Working on this book led to writing “Rethinking the City with Bourdieu’s Trialectic” published in the journal City (2023). See also my interview “Penser l’urbain avec Bourdieu” (published in Métropolitiques and several languages, including ). See also the symposium on the book in Dialogues in Human Geography, including my response “What Bourdieu Tells Us about the City and the City about Bourdieu” (2024); and the symposium in French in Métropoles to which I respond in “Bourdieu de ville et Bourdieu des champs” (2025).

ETHNOGRAPHIC EPISTEMOLOGY AND METHODOLOGY

Misère de l’ethnographie de la misère (The Poverty of the Ethnography of Poverty, published by Raisons d’agir Éditions, “Cours et travaux,” 2023) is a book of ethnographic epistemology, theory, and advocacy: a critique of ethnographic reason. It recapitulates the three ages of “urban ethnography” over a hundred years to extract its roots in a philosophy of knowledge and action characterized as “moral empiricism” that turns out to be profoundly anti-sociological. The book makes a plea for an enactive, structural and historicized ethnography that is at once more theoretical and more deeply embedded, socially and symbolically, and it warns against he trap of “ethnographism” and its five associated fallacies. It develops the Bourdieusian notion of “thick construction” against the two reigning models of ethnographic practice, Clifford Geertz’s “thick description” and “grounded theory” à la Glaser and Strauss, while also marking its difference with the extended-case method and abductive theorizing.

MEM is coming out in English as The Poverty of the Ethnography of Poverty with Oxford University Press in the July of 2025 with a gorgeous cover, a painting by Romare Bearden I had wanted to use for years for one of my books

I drew the main ideas of PEP together in the article “In Praise of ‘Thick Construction'” published in Qualitative Sociology (2025). The article is a topic of a symposium with contributions from Katie Jensen, Neil Gong and Josh Seim, to which I respond in “Catching the ‘Epistemological Virus’.”

ETHNORACIAL DOMINATION: EPISTEMOLOGY, THEORY, WORLD HISTORY

Race is arguably the single most troublesome and volatile concept of the social sciences in the early 21st century. It is invoked to explain all manner of historical phenomena and current issues, from slavery to police brutality to acute poverty, and it is also used as a term of civic denunciation and moral condemnation. In Racial Domination (published in summer of 2024 with Polity Press), I mine comparative and historical research from around the globe to pours cold analytical water on this hot topic and try to infuse it with epistemological clarity, conceptual precision, and empirical breadth.

Drawing on Gaston Bachelard, Max Weber, and Pierre Bourdieu, I first articulate a series of reframings, starting with dislodging the United States from its Archimedean position, needed to capture race-making as a form of symbolic violence. I then forge a set of novel concepts to rethink the nexus of racial classification and stratification: the continuum of ethnicity and race as disguised ethnicity, the diagonal of racialization and the pentad of ethnoracial domination, the checkerboard of violence and the dialectic of salience and consequentiality. I also offer a meticulous critique of such fashionable notions as “structural racism” and “racial capitalism” that promise much but deliver little due to their semantic ambiguity and rhetorical malleability—notions that may even hamper the urgent fight against racial inequality.

The second part of the book turns to deploying this conceptual framework to dissect two formidable institutions of ethnoracial rule in America: Jim Crow and the prison. I draw on ethnographies and historiographies of white domination in the postbellum South to construct a robust analytical concept of Jim Crow as caste terrorism erected in the late 19th century. I unravel the deadly symbiosis between the black hyperghetto and the carceral archipelago that has co-produced and entrenched the material and symbolic marginality of the African-American precariat in the metropolis of the late 20th century. I conclude with reflections on the politics of knowledge and pointers on the vexed question of the relationship between social epistemology and racial justice.

Some of the core propositions of Racial Domination are elaborated in “Resolving the Trouble with ‘Race” (published in the New Left Review in 2023). Seven papers applying this framework are “The Trap of ‘Racial Capitalism'” and “Racial Capitalism Decoupled: A Rejoinder and Reformulation” (Archives européennes de sociologie, 2023, symposium with responses from Gurminder K. Bhambra, John Holmwood and Sanjay Subrahmanyam); “The Radical Abdication of Afropessimism” (New Left Review, 143, Sept-Oct 2023); “Checkerboard of Ethnoracial Violence” and “Race in the Violence of Violence” (Contention, 11/2, 2023 and 2025), symposium with responses from Robert Braun and Scott Straus, Aliza Luft, and Ali Meghji); and “Notes on Race as Denegated Ethnicity” and “Farewell to ‘Race and Racism’: On the Analytic Priority of Ethnicity” (Ethnicities, 2025) symposium with responses from Magali Bessone, Karida Brown, Stephen Cornell and Douglas Hartman, Aryan Karimi and Rima Wilke, and Andreas Wimmer

CASTE TERRORISM: AN EXERCISE IN HISTORICIST-ANALYTICAL SOCIAL SCIENCE

I have long held a sociological fascination for the regime of racial domination in the post-bellum South of the US known under the moniker “Jim Crow.” Racial Domination devotes a chapter to it as a case illustration of the agonistic theory of race-making. But that did not dig deep enough so I expanded and turned this chapter into a book of its own entitled Jim Crow. Le terrorisme de caste en Amérique, published in April 2024 by Raisons d’agir Éditions. We associate the notion of caste with Brahmanical India, but in the American South between the 1890s and 1960s, blacks, descendants of slaves, were treated as a outcaste, veritable “untouchables” in the land cradle of democracy. Jim Crow is the name commonly given to the system of racial domination that held them in its ferocious grip, and against which Martin Luther King’s Civil Rights Movement surged. But what exactly was it, and how did it work? Was it just “segregation from cradle to grave,” “whites-only” water fountains and bus seats, black convicts toiling in leg irons and episodic lynchings, as is generally believed?

I draw up a meticulous historical accounting aimed at constructing a rigorous sociological model of this regime. I show that, backed by the myth of “one-drop rule,” it consisted of four closely interwoven elements: an economic infrastructure of sharecropping morphing into debt peonage; a social structure of institutional duplication and the demand for permanent black deference to whites; and a superstructure of political and judicial disenfranchisement. But African Americans never acquiesced to these three mechanisms of exploitation, subordination and exclusion. So these had to be secured by a fourth element, terroristic violence, a protean violence (intimidation, assault, rape, manhunt, pogrom, whipping, lynching and public torture, but also arbitrary arrests, abusive incarceration and hasty executions carried out by the law) that hovers over every social interaction between whites and blacks and can strike at any time with impunity to communicate a strident political message: the imperiousness of white supremacy. The book reengages the questions of caste and race, the Southern Sonderweg and its historical alternatives, and stresses the historicity of racial domination, that is, the need to understand its forms and mechanisms in their specificity for scientific and civic reasons.

2024 ADORNO LECTURES: RETHINKING THE PENAL STATE

In November 2024, I gave the 2024 Adorno-Vorlesungen in Francfort. The topic of the lectures was “Rethinking the Penal State.” The first lecture drew on social theory: “Penality as Core State Capacity and Negative Sociodicy.” The second lecture drew on social history: “Marginality, Ethnicity, Territory” (including an excursus on colonial penality). The third and last lecture drew on ethnography: “Penal Power Incarnate: A Day in the Life of a Prosecutor.” I am now revising into a book entitled Rethinking the Penal State to be published early next year in German by Suhrkamp and English by Polity Press. You can view the lectures on the YouTube channel of the Institut für Sozialforschung:

Lecture 1: “Penality as Core State Capacity and Negative Sociodicy.“

Lecture 2: “Marginality, Ethnicity, Territory.”

Lecture 3: “Penal Power Incarnate: A Day in the Life of a Prosecutor.”

I could not squeeze a long excursus on the role of the penal state in European colonies in the lectures. So I wrote an article entitled “Punish to Rule: Colonial Penality and the Urban Badlands” (published in the New Left Review in April 2025).

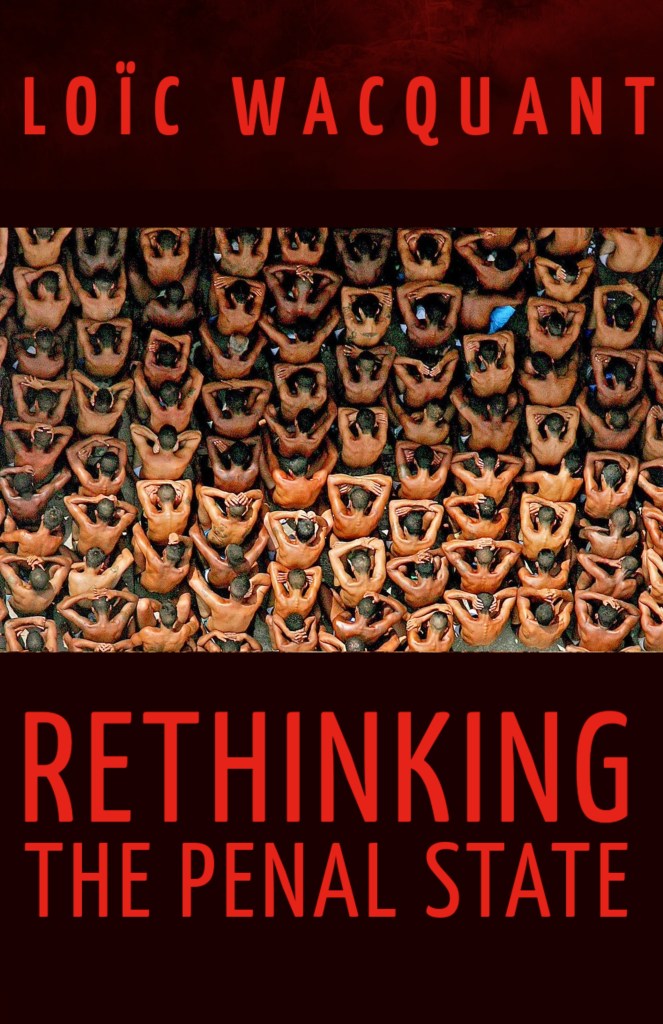

Here is a brief presentation of the book and its working cover (isn’t it arresting? The caption below is worth a read).

In this book based on 2024 Adorno Lectures, Loïc Wacquant combines social theory, comparative history and structural ethnography to probe criminal punishment as a core function of the state. Extending Pierre Bourdieu’s signal concepts of bureaucratic field and symbolic power, Wacquant resolves the opposition between rationalist theories of penality running from Bentham to Marx and emotionalist theories descending from Kant to Durkheim to capture the constitutive duality of punishment, at once material and symbolic, an instrument of class control and a means of communicating values, endlessly oscillating between rehabilitation and retribution.

By rolling out the police, court, prison and their bureaucratic tentacles, the penal state curates crime, contains moral disorders, manages urban marginality and draws the boundary of citizenship. Its day-to-day deployment also signals sovereignty and serves to manufacture political legitimacy in the eyes of the law-abiding population. But the penal Leviathan is a bifurcated state which captures nearly exclusively dispossessed and dishonored populations by targeting their neighborhoods: it is everywhere a class-splitting and a race-making institution based on the stubborn differentiation of “paper penality” and “street penality.” The structural osmosis between districts of urban dereliction and the carceral institution on both sides of the Atlantic is such that we cannot understand the penal state without understanding the dual city and vice versa.

To flesh out penal power as strategic action, Wacquant takes us deep inside a criminal court in California where we discover that the prosecutor who negotiates guilty pleas is the human spear of the state. In his daily tussles with defense attorneys and the sentencing judge, he calibrates and drives the concrete infliction of physical and psychic force upon bodies deemed out of order. Getting inside the machinery of criminal justice shows that punishment must be placed at the epicenter of the political sociology of statecraft, group-making and place-making in the metropolis as well as brought to the forefront of civic debate, rather than abandoned to the periodic panic-peddling of electoral politics. Instead of chasing the chimera of abolition, we should muster the intellectual resources needed to reclaim the vexed duality of “law and order” for a progressive politics. This requires articulating a radical penal minimalism suited to reconciling punishment and democratic citizenship.

CAPTION FOR THE COVER: Packed inmates stripped to their underwear sit prostrated in the prison yard under the fierce watch of the military “shock units” called in to put down the carceral riot at Franco de Rocha, Greater São Paulo, in May of 2006. The riot was one in a wave of coordinated attacks around the state orchestrated by the criminal mega-gang Primeiro Comando da Capital (PCC) against law-enforcement institutions in retaliation for the transfer of their leaders to high-security penitentiaries and to demonstrate their de facto control of penal facilities. The attacks included coordinated revolts in 83 prisons, with widespread destruction and hostage-taking, the targeted killings of police, and the firebombing of city buses and public buildings as well as hundreds of assaults on police stations, courts, fire departments, hospitals, schools and banks, causing some 170 deaths and generating a climate of chaos and terror for five days. According to human rights agencies, over 500 people, most poor young men of color from the urban periphery, were later killed in police retaliation, upwards of 100 victims of summary executions. (For an analysis of the rise of the PCC and its role in organizing this direct challenge to the penal state, read Bruno Paes Manso and Camila Nunes Dias, A Guerra. A Ascensão do PCC e o Mundo do Crime no Brasil, São Paulo, Todavia, 2018).

This episode captures both the brutal power of the penal state and direct defiance of the same, triggering the seemingly uncontrolled but actually targeted resort to force, legitimate or not. It ties together penality, marginality and dangerosity. And it reminds us of what citizens in advanced societies take for granted: that violence is under control, the streets peaceful and one can go about one’s business without fearing for life and limb, and that the Leviathan acts in accordance with legal standards and rules.

Photo by Paulo Leibert/Agência Estado.